When I interview financial advisors in Canada, a few consistent themes rise to the surface when we talk about investing.

Things like “Canadians aren’t using tax vehicles to maximize returns.” And “Canadians need to include more in their TFSAs.” And of course, this one is great: ‘Don’t contribute to your RRSP at the last minute!’

Another topic is “holistic planning,” which came up during conversations with Janet Gray and Steve Bridge of Money Coaches Canada. That is, considering all areas of the client’s finances (investments, pensions, taxes, insurance, short and long term goals, etc.) brought together in a complete financial plan.

There are also “things to avoid” that come up during these conversations. These are the three main investment mistakes mentioned:

1. Not investing early enough

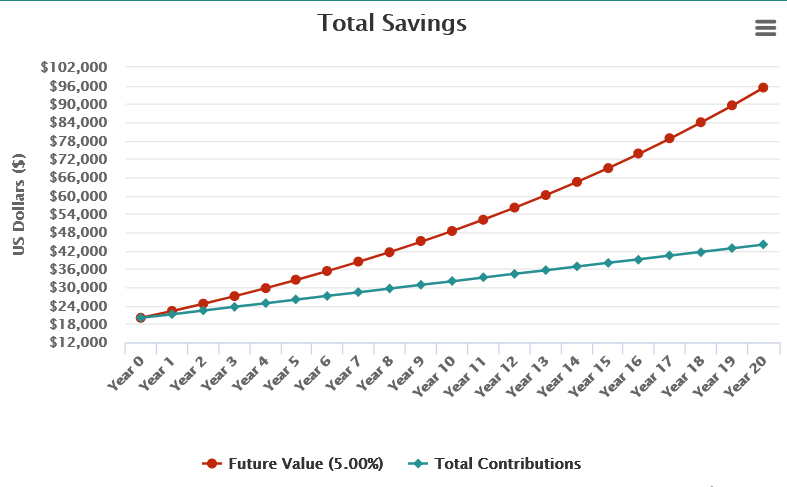

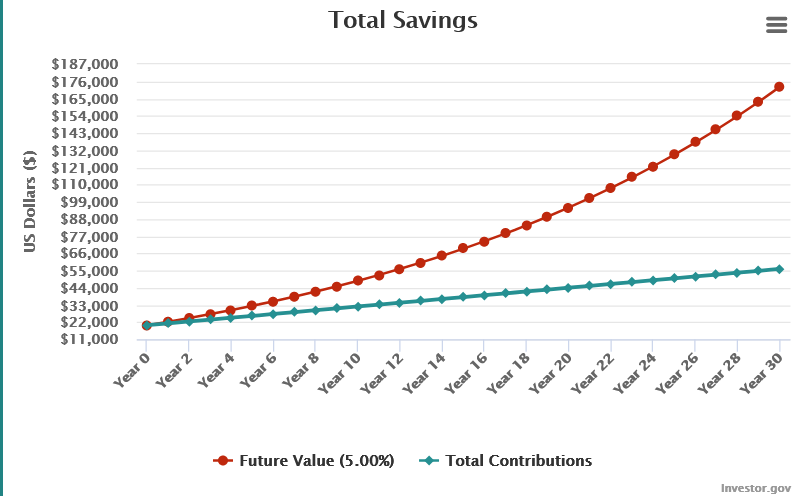

While we can’t use time machines, the second best time to invest is today. The power of compound interest will continue to prevail. And we can help educate those who may be younger than us with illustrations. For example, Ally, 27, and Garcia, 37, begin their investment journey with $20,000 each, with the plan to withdraw the funds at age 57. They both invest $100 per month, which is compounded monthly, at an annual rate of 5%. return.

In 20 years – García will have $95,356.17

In 30 years – Ally will have $172,580.75

That’s almost double, but Ally only invested an additional $12,000 because of the 10-year difference. I find these results surprising and think it would be worth sharing these graphs with family members or younger clients to illustrate the power of compound interest. And the real value of starting investing early. Time is money and it is truly the best tool we have to generate wealth.

2. Getting in our own way (aka behavior)

Impulse purchases can lead to purchases at the least opportune time. In Morningstar’s most recent Mind the Gap study, we learn that can cost us a fifth of our returns.

Our annual study of dollar-weighted returns (also known as investor returns) finds that investors earned about 6% annually on the average dollar they invested in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds over the past 10 years ending 31 December 2022. is approximately 1.7 percentage points less than the total returns generated by its fund investments during the same period. This shortfall, or gap, is due to ill-timed purchases and sales of fund shares, which cost investors about one-fifth of the return they would have earned if they had simply bought and held.

This pattern is consistent year after year in these studies. Investors fared the worst in stock funds in the industry, losing more than 4 percentage points per year due to poorly timed fund flows.

This is another case that makes investors who seek profitability sigh. Trying to buy low and sell high, but it doesn’t work. Magic happens in the most boring way…when you buy and hold. It’s not sexy, but it works.

3. Paying annoyingly high fees

Canadian investors continue to pay some of the highest fees in the world, especially when it comes to mutual funds. In the most recent report on global investor experience, Canada scored below average.

Janet Gray suggests Getsmarteraboutmoney.ca to help with issues like determining exactly what you’re paying:

You may pay a sales charge when you buy or sell units or shares of a fund. These sales charges are also known as loads. Funds can be offered with a front load, a back load, a low load or no load. These sales charges are set by the mutual fund company.

Fortunately, some of the most egregious fee grabs have been banned, such as the recent ban on deferred sales charges (DSC).

How to reduce your rates:

- Consider a fee-based account, so you don’t pay a sales charge when buying and selling funds, it’s a client advisory fee.

- Know exactly what you are paying for and read the fund’s prospectus carefully.

- Do your research on investment fees and costs.

- Keep in mind that when receiving financial advice through a bank, advisors are strongly incentivized to sell the bank’s own line of mutual funds, which are more lucrative for banks than lower-priced products like ETFs.

- If you work with an advisor, ask them the total cost you pay. Not only the advisory fees, which are included in the annual fee statement, but also the cost of the product and any other charges. Then ask yourself: Am I getting value for these fees?

- Finally, fees may be on the higher end of household expenses on an annual budget. For example, if you have $500,000 invested and pay 2% in fees, that’s $10,000 a year. Rates are very important to your overall results.