The new state budget underfunds pensions and hand out benefits lavishly. It cuts pension contributions by $670 million and spends $702 million on district subsidies. Neither of these things benefit the public.

Elected officials accidentally turned school employees into the state’s largest creditors. Lawmakers required teachers to participate in a state retirement system, but they didn’t set aside enough money to pay their pensions. That’s unfair to both teachers and taxpayers. It’s not as if school workers volunteered to lend the state money. The state now owes teachers $29.9 billion more than it has saved. That’s more than the state owes bondholders who voluntarily loaned it money.

In recent years, lawmakers have been catching up on what they need to pre-fund retirees’ health insurance costs. This year, they decided to take the money they had been spending to pre-fund those benefits and spend it on their other priorities. That $670 million might have reduced some of what is owed.

Instead, it’s being spent on other things, and lawmakers are letting school districts pocket some of the underfunding. Pension contributions are split between the state and school employers, and lawmakers will ask school districts for less next year. And lawmakers will also stop asking current employees to contribute 3% to pre-fund their retiree health care benefits and have taxpayers cover that cost instead. This shifts the cash freed up by underfunding the pension system to school districts and school workers.

This is a short-sighted strategy. Pension debts are mounting like any other unpaid liability. It might make sense to defer them if there was a pressing need. In this case there wasn’t. It was a request from the teachers union, whose members will get some extra money in the short term and apparently ignore the long-term costs.

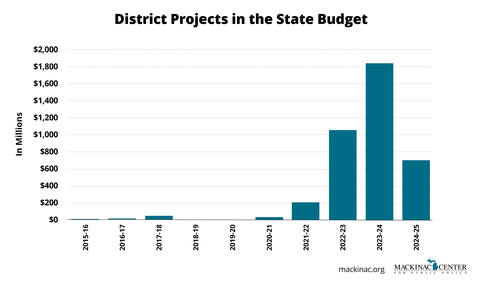

Another top priority for lawmakers was taking taxpayer revenue and redistributing it to projects in lawmakers’ districts. The budget contains 415 specific line items spending $702 million.

District grants are wasteful because they allocate money to promote the interests of one legislator rather than the interests of the state as a whole. State government is supposed to spend the public purse in ways that best serve the public, and legislators have broad discretion to decide that.

While lawmakers constantly demand that money be brought to their districts, they do not have to give in to the wishes of their base. Previous budgets did not contain so much superfluous spending. The explosion of grants to districts only began three years ago.

Lawmakers know they are doing something wrong. Otherwise, district grants would be part of the executive budget and the budgets initially passed by the House and Senate, rather than a last-minute addition.

There are supposed to be protections against district grants. The state constitution requires approval by two-thirds of legislators for giving money to local and private interests. This flies in the face of the provincial interest in having legislators look out for their direct constituents rather than the general public.

However, lawmakers have a loophole to get around that requirement. They don’t directly state who the recipient is, but instead use population requirements that apply to a single entity. Consider how lawmakers allocated money to Berston Fieldhouse in Flint. The money “shall be awarded to a city with a population between 81,000 and 82,000 in a county with a population between 400,000 and 500,000 according to the most recent decennial census to support infrastructure improvements to a sports stadium.” No other city in Michigan had a census population in that range except Flint. No other county in Michigan had a census population in that range except Genesee County.

Perhaps the project could have been the state’s largest if lawmakers had established a grant program to fund community centers. Or maybe not.

It’s idealistic to want legislators to create budgets in the public interest, but the Constitution is an idealistic document. People should want their legislators to meet high standards, for the state to catch up on what it owes to retirees, and for the state to spend the public purse for the benefit of the public.

Lawmakers have fallen short of ideals with their latest budget.

Michigan’s 2025 Budget